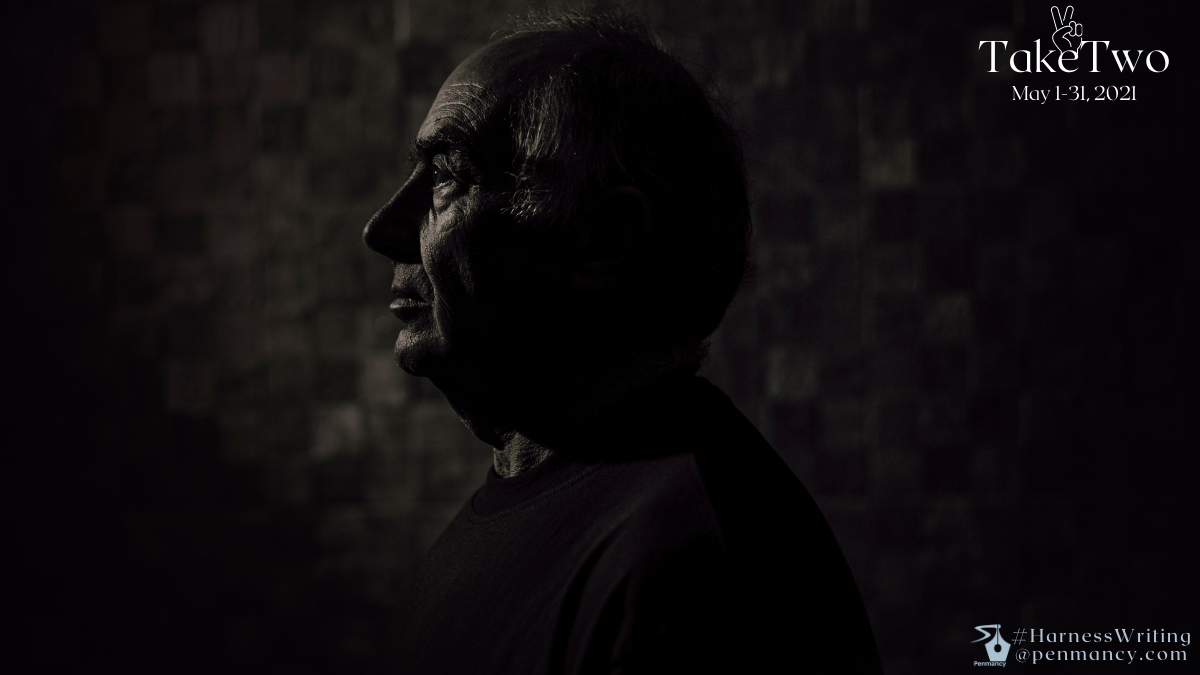

The common man, my unsung hero

Today was the fifteenth day of our beloved Grandma’s passing away. In the evening, after tea, Grandpa had asked us to gather in his room. We contemplated various reasons for the assembly. Our excitement and speculation continued throughout the day.

My brother and I, along with our first cousin, huddled around Grandma’s side of the bed. My parents; my father’s own younger sister with her husband; in relation, my aunt and uncle, sat on the chairs and settee. The atmosphere was a little strained due to the disagreements in the opinions between Grandpa and his children.

On hearing the news of Grandma’s sudden massive heart attack, our parents rushed from Delhi to Bangalore. Our aunt followed suit from Bombay. It was all over within a day. My brother and I joined later before the thirteenth-day rituals took place. He had to submit his school projects; within the deadlines for the finals, and I had to complete my college semesters. Our cousin and his dad arrived; also on the same day as ours. From the discussions and conversations held amongst the elders, we grasped the tensions which brewed; inside the boundaries of this bungalow, where our grandparents lived for the past fifty years.

“This is the legal bequest signed by your mother and me.” Grandpa placed it on the table between the seats of my father and aunt.

“This can wait.” My father stated in a cold tone.

Aunt chipped along with Dad, “Why do you have to discuss this now?”

“I have to update all of you; regarding some facts. I had not spoken about it earlier; due to the promises of your mother.”

“When we come back next time, we can consider these, but not now.” Aunt was vocal.

“No. You are leaving the day after tomorrow. My days are; numbered. In your busy lives, before I lose the opportunity, I want you all to know about the truths of our lives.”

My mother called out to us, “Come, let us set up the dinner table; in the meantime. They will join once their discussions are over.”

“You’re a part of this family and not a stranger. I think; your mother-in-law and I have treated you nothing less than our daughter. Please stay, and also the children are grown-ups now, in their late teens. They are entitled to know their family history.”

I intervened, “Grandpa, please go ahead with your narratives.”

“Dear, it was long ago,” he smiled at me, “I was a student at a small school in one of the remotest villages of Bengal. My father was a boatman, who transported goods and men from one shore of the village towards the town.”

“Where was your mother? Did you have brothers and sisters?” My cousin intervened.

He continued, “We all lived together in the village, till I headed with a full scholarship to the city college. It was the pre-Independence era. All our young minds were influenced; by the speeches of the national leaders. The spirit of patriotism and freedom of our country seethed within us. I joined the college group and took part in protests against British atrocities and all social evils. We ensured no cruelties were committed; against women like child marriages and dowry deaths.”

“Such a dark age.” My brother mused.

“I finished college and got a job as an accountant in the city of Calcutta. It was a fulfilling moment for me, as my large, struggling family back in the village was in dire necessity of financial assistance. My success was overshadowed; by the social milieu. The country was burning from communal riots and freedom struggle. The wildfire engulfed houses and people, so I decided to bring my family to the city where I lived; before they bear the brunt of it in our small village. We quietly packed and prepared for our escape route.”

“This sounds like a fast-paced action film.” I looked in awe at my Grandpa, his only granddaughter, a favourite of my grandparents, the eldest among the grandchildren.

He grinned, “The culmination is yet to come. Hold tight. The day we fled, the other side of the village already bore the impact. In the darkness of the night, the raging flames danced all around us. My family members, with their minimal possessions, boarded our boat. I was the last one to arrive. They waited for me as we cautiously exited one by one from our hut so as not to arouse any suspicion in the minds of the neighbours or the moles.”

“We’ve heard about the Partition stories and the plight of the people. Is there any reason that you’re repeating the past?” Aunt restlessly asked.

Grandpa sternly looked and proceeded, “I entered the boat with a young girl with large black eyes, long dark hair, a dishevelled look, dressed as a bride. My family was startled. We sailed and came to the town, from there we got on a bus to the city. We all settled in my single rented room in an old, dilapidated house, located in one of the narrow, by-lanes of central Calcutta. The owners were an elderly couple who lived on the top floor. We shared a common bathroom with them in the courtyard downstairs and did not have a proper kitchen. We had to make do with a temporary shed on the corridor, where the earthen furnace got ignited and meals cooked day and night, to feed half a score of my family.”

“Who was that girl?” My brother queried.

“I was briskly walking past the village fields towards our boat when I heard wails from a nearby house. On a closer look, I found a young girl dressed as a bride, stood in front of a dead man, along with other people. An elderly lady hugged the impassive girl. She begged others to pity her and save her life. I was horrified at this revelation. Fury overpowered me, and without a second thought, I lit the haystacks and the fire erupted and engulfed the house. Everyone ran helter-skelter. The smoke clouded the dark night. I dragged the girl along with me; to the shore, where our boat with my kin awaited.”

Grandpa paused and drank the water from the bottle. He cleared his throat, a faint signal about the emotional turmoil that accumulated in the crevices of his mind.

“All hell broke loose after a few days. My mother vehemently protested the anonymous village lass residing with us. Her outrage and prejudices were justified; during those times. The girl was a widow, belonged to a higher caste, not related to us, and the city neighbours’ prying eyes, queries and gossips, made my mother irritated. It was also becoming increasingly difficult to sustain so many mouths with one measly income of mine. The frayed nerves were exhausted in the crammed one-room, with no privacy within the inmates.”

The darkness of the evening was setting in. My mother switched on the lights and lit the lamp near Grandma’s photo frame. Everyone folded their hands and showed their reverence to the departed soul.

“I was aware of the fact; that the stark contrast between the rural and city life was a daunting challenge to adapt; for all. Within a day, we lost our soil, the vegetation, the clean, fresh air, the ponds, the muddy routes, and the endless free space of greenery in our village. What an irony; we fought for the independence of our motherland at the cost of losing our own roots. Our uncertain, bleak futures stared and mocked at us in sarcasm.”

“Such a sensitive situation you had to face, Grandpa.” I empathized with him.

Grandpa nodded, “I assured my mother that as soon as I get information about a good shelter-home for women, I would enrol the girl. More than a month passed, the family was gradually settling down to their unpredictable fate. My father got a job as a dockworker to haul goods from ships, and my mother became a cook in a couple of nearby houses. My younger brothers and sisters went to the free government school and college nearby, a ten-minute walk from our rented place. The girl stayed at the house and completed the household chores.

Grandpa’s recurrent cough started. Uncle suggested, “We can take it forward tomorrow; if you want to relax now.”

He disagreed and, after a while, began his tale again. “All the males of our family slept on the corridor, outside the room, and the females inside the room. I never entered the room when she was alone. I noticed that day after everyone left, neither did she step out of the room to take a bath, nor was she busy with; the cooking and cleaning. Usually, I left late as my office work started after ten in the morning. A muffled sound floated from the dark interior. The door was not locked, so I knocked and peeped inside.”

“Grandpa, I want to go to the restroom; please hold on to it.” My cousin, all of sixteen years old but still a kid at heart, interrupted. All eyes were focussed on him with irritation, though it was a good, short break for all of us. We took advantage of the situation and paid a visit to the restroom, including Grandpa. My mother and aunt dictated to the maids about the food to be cooked for dinner. Everyone settled back to their respective places after fifteen minutes.

“Where was I? Ah, yes! I sensed the tears flowed; her body trembled, her back towards me, as she sat at the edge of the bed. I pacified her through my limited vocabulary but firmly egged her for the cause of her sadness. My unsuspecting mind thought that she was depressed due to her traumatic circumstance. She was alone in a foreign land, had no relatives, and lost everything at such a tender age. Ultimately, she blurted, that death was a boon to her, and my gift of a second chance to live her life had become a bane in her existence. I was appalled at her confession. On probing further, the narration gave me a bolt out of the blue. I froze at her disclosure. For a long time, I couldn’t decipher my deeds that followed.”

We sat up and crouched near our Grandpa for better visibility of his face and audible rationales. We didn’t want to miss a single word pouring from his lips. Repetition was not his cup of tea which signalled our inattentiveness.

“India, at last, gained its Independence. A celebratory mood was in the air. A few days later, on a weekend evening, I bought the tickets and sent my whole family to watch the Bengali film, “Harishchandra”. In the absence of everyone, I wrote a letter to my father, kept my monthly salary, and left the house with the innocent girl. On our way, we got married at a temple; and boarded the night train to Madras.”

We gaped, shell shocked with the flow of the narration.

Grandpa was unaffected by our reactions. “My organization had a small office in Madras, and no one wanted to travel and settle there. I had a lengthy discussion with my Calcutta supervisor and took over the job. From there, Asha and I started our new life as husband and wife. Every month, I sent most of my salary to my family, on Asha’s insistence. She started stitching, sewing and knitting at home for neighbours and supplemented our meagre means. She was indebted to all of us for getting a fresh lease of her life on that fateful night.”

“Ma and you; had good cordial relations with your brothers and sisters. That’s what we have seen as we grew up. It was always a big, happy family reunion whenever they visited us in Bangalore or when we went down to Calcutta. Though by that time, your parents were no more, and we stayed at uncles’ or aunts’ houses.” My aunt blabbered, astonished. “How come Ma or no one else mentioned this to us, ever?”

“Be patient. I have not completed the full story yet.” Grandpa admonished Aunt. “It wasn’t love at first sight for both of us. I rescued her from that gruesome incident, and she was grateful for my valour. Asha and I knew that we would not be accepted in our family, never, ever. There was a hidden truth for which we had to take this drastic step. I had to leave all of them and be by your mother.”

Grandpa paused; the room bore a tight stillness. The sound of our intense breath resonated. He looked up at Grandma’s picture frame on the wall and addressed her.

“You’ve been my strength for all these years. Your sacrifice, care and respect for not only the loved ones but also outsiders were highly commendable. You knew I always upheld my ethical standards and never compromised on my integrity. For so many years, I have hidden this secret from our family; because you made me promise not to reveal it as long as you lived in this mortal world. You were scared; that similar to our families again, this family would get disintegrated because of you. You were frightened to lose anyone as you had lost all your near and dear ones; throughout. Today, let me unburden my soul; forgive me.”

Quickly, I added to ease the atmosphere, “All’s well that ends well. Grandma and your struggles finally paid off. Gradually, with a good job at HAL, you settled in Bangalore. You built this bungalow at Indiranagar. We all were born and grew up here, till dad and aunt shifted to different places due to job and personal requirements. Your extended family accepted your relation with Grandma in the later period. You both had a blissful union and a happy fifty years of your married life. Grandma is content wherever she is now and also blessing us from her eternal abode.” I beamed at him.

“Hmmmm, yes, before I forget, in the legal will, Asha and I have provided our signatures in front of our lawyer; the other copy is with him. We have divided all our assets between both of our children equally. After my demise, this house will belong to my son and the other one at Jayanagar to my daughter. All the money kept in Fixed Deposits and shares has been divided equally between both of you, as nominees.”

An impregnable silence ensued. At last, my brother spoke softly, “Grandpa, why did you leave Calcutta? You could have rented another house there and stayed with Grandma, far away from your parents.”

“Intelligent boy! Yes, I haven’t finished the climax.” He chuckled.

“Your Grandma belonged to a high caste Brahmin family, unlike us, who belonged to the lower caste of the Bengali Hindu society. She was married off at the delicate age of sixteen and had stayed for six months in her first husband’s house; before his untimely demise due to pneumonia. He was thirty years older than your Grandma and his third marriage. His earlier wives had passed away during childbirth and had left behind some of his children. The orthodox family wanted your Grandma to perform Sati and; die as a bride with her deceased husband instead of living a widowed life. Her mother was the only person who pleaded for her daughter’s life, but without fruition.”

“What?!” I screamed.

Pointing to the picture, Grandpa asked us, “Now, do you comprehend, why I resented the last rites of Asha’s funeral on the flames of a pyre? She was saved from it once, at the nick of time. Later, she suffered from pyrophobia, so I became protective of her. I decided that under any circumstances, her body will not follow our religious practices but donated for the benefit of mankind and scientific research.”

I pursued, “Sati got abolished a long time back. Raja Rammohan Roy, considered to be ‘The Father of the Bengali Renaissance’, fought tirelessly to eradicate the practice of Sati in India. How could they continue this heinous act after so many years?”

He agreed, “I also worked on the principles of Vidyasagar and organized widow remarriages. In every nook and corner of the society, there still is some sinful act lurking, spearing its ugly head and extending its fangs to throttle societal progression.”

My cousin became impatient and said, “Grandpa, why are you deviating?”

“Ok, let me continue with our story. The reason for us to leave Calcutta was, your Grandma contemplated suicide; due to her physical condition, which she was not aware of earlier. She realized that she had conceived and was two months pregnant with the child of her first husband. On hearing this, I immediately decided to marry her and relieve the young, petite lady of her untold agony and misery. Asha denied my pronouncement at once. She was scared and rationalized about the societal and familial taboos. I had lots of arguments with her. Later, she obliged my firm decision. We left everyone and everything in Calcutta for the safety and security of the unborn child.

Monosyllabic words of disbelief escaped from all our lips.

Grandpa with a serene face, looked at me and said, “Asha gave birth to our son, your father, in Madras. After seven years, we had our daughter in Bangalore.”

The whirring of the fan was louder in the stunned silence of the room.

My mother, at last, got up and broke the silence. “It’s quite late. Let’s have dinner, now.”

One by one, they left the room without a word. I was the last one to leave, but instead turned back and went straight to my Grandpa. With a tight hug, I whispered, “Today, I’m proud of a common man; you will always be my unsung hero, my Grandpa.”

Glossary –

Sati - was a historical Hindu practice, in which a widow sacrifices herself by sitting atop her deceased husband's funeral pyre.

Raja Ram Mohan Roy - (22 May 1772 – 27 September 1833) was one of the founders and precursor of the Brahmo Samaj, a social-religious reform movement in the Indian subcontinent. He was known for his efforts to abolish the practices of Sati and child marriage. Raja Ram Mohan Roy is considered to be the "Father of the Bengal Renaissance" by many historians.

Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar - (26 September 1820 – 29 July 1891), born Ishwar Chandra Bandyopadhyay, was an Indian educator and social reformer. He was the most prominent campaigner for Hindu widow remarriage and petitioned Legislative council despite severe opposition.

Penmancy gets a small share of every purchase you make through these links, and every little helps us continue bringing you the reads you love!